Daniel Parker looks at the Worker Protection (Amendment of Equality Act 2010) Bill, what it means for employers and what it says about changing attitudes to harassment.

Despite its anodyne name, the Worker Protection (Amendment of Equality Act 2010) Bill is draft legislation with potentially significant practical implications for employers. As it has passed through the House of Commons with Government support and has recently received its second reading in the House of Lords with cross-party backing, now is an apt moment to reflect on the Bill and what it says about how we protect against workplace harassment.

At present, the UK’s tentpole discrimination statute, the Equality Act 2010, protects workers from harassment by colleagues, but not third parties (such as clients or customers, for example). That was not always the case, however; as initially introduced, the Equality Act contained provisions relating to third party harassment. Despite significant opposition – from 71% of respondents to the official consultation – in 2013 the then-Government repealed those initial third-party harassment provisions, on the basis that there was ‘no evidence to suggest that [they were] serving a practical purpose’ and that employers could be encouraged to ‘do the right thing’ by other means.

Our understanding of harassment has since developed considerably and attitudes in Government as to how to address harassment appear to have changed. If agreed by the House of Lords, the Bill would make an employer liable where:

- a third party has harassed an individual in the course of their employment; and

- the employer has failed to take all reasonable steps to prevent that from happening.

Those are more restrictive grounds for liability than if the harassing conduct is carried out by a colleague, but it nevertheless represents a considerable shift in the legislation.

There are other limits on employer liability, which apply unless the harassment is sexual. Employers will not be seen as falling short merely because they fail to prevent a third party expressing their opinion if:

- the harassing conduct is not aimed at the employee or part of a conversation they are involved in;

- it involves the expression of an opinion on a political, moral, religious or social matter;

- the opinion is not indecent or grossly offensive; and

- it does not have the purpose of violating the employee’s dignity or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for the employee.

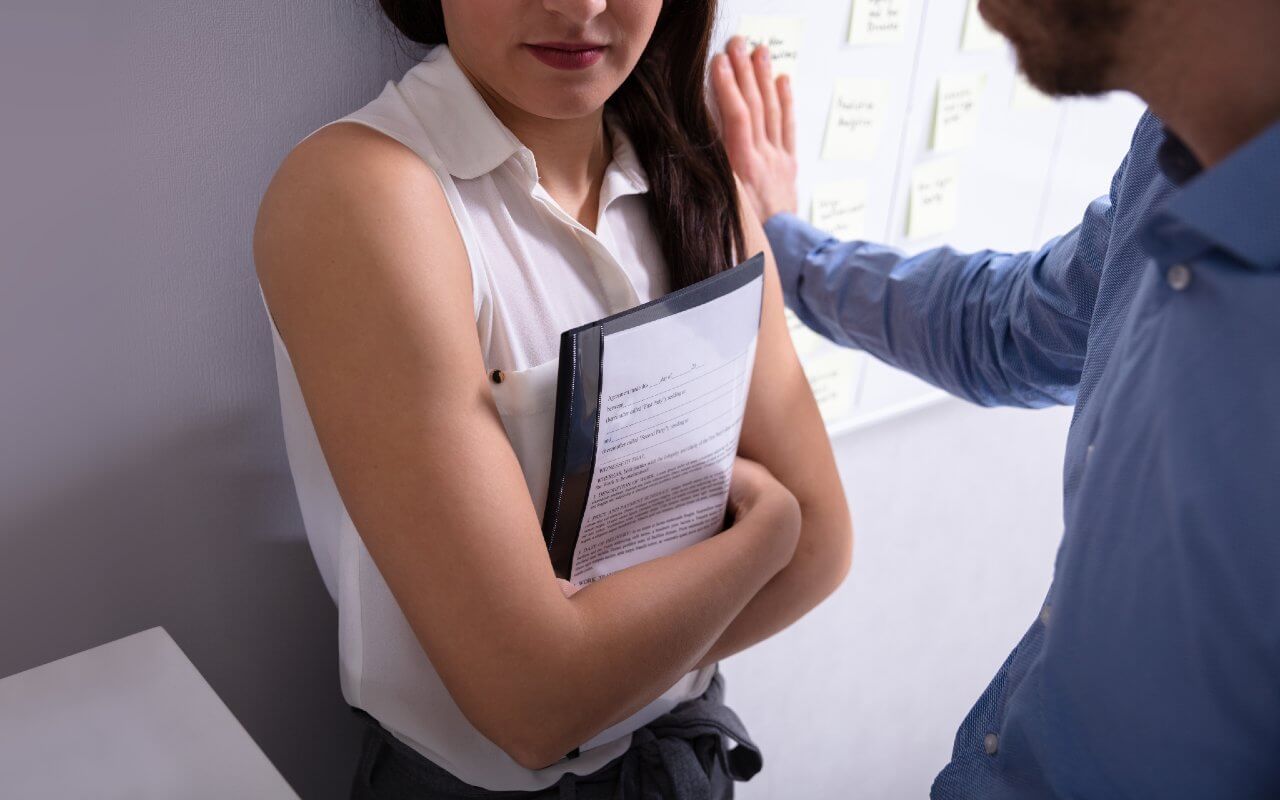

In addition to the developments regarding third party harassment, particular treatment is reserved for sexual harassment under the new Bill. Again, insofar as sexual harassment is carried out by colleagues, this is already prohibited by section 26(2) of the Equality Act 2010. However, the #MeToo movement has brought into sharp focus the extent and impact of sexual harassment in the workplace and invited further scrutiny of whether existing approaches are sufficient to combat it.

In 2019, the then-Government launched a consultation on the issue of sexual harassment in the workplace. When the consultation concluded in mid-2021, it highlighted that there is ‘still a real, worrying problem with sexual harassment at work, as well as in other settings’. In response, it was agreed that a new duty to prevent sexual harassment at work would be introduced, with the aim of incentivising employers to ‘prioritise prevention’.

This is now reflected in the proposed Bill, which requires an employer to take all reasonable steps to prevent harassment of their employees in the course of their employment. Breaching the duty will not give an individual a standalone claim. Instead, the role of enforcement will be given to the Equality and Human Rights Commission, whose guidance is likely to be an important reference point for employers. However, where an Employment Tribunal has found an employer liable for sexual harassment and has awarded compensation, the Tribunal will be under a duty to consider whether the employer has also breached its duty to prevent sexual harassment and, if so, may order an uplift in compensation of up to 25%, thereby increasing the financial risk of such claims.

When addressing the consultation in 2021, the then-Government acknowledged the concerns of some respondents that this preventative duty was unlikely, without more, to fully address the issue of sexual harassment at work. However, its response was that the new duty would be an ‘important and symbolic first step’. When contrasted with the deregulatory focus of the previous decade, during which the Government rolled back harassment protections, this remark shows perhaps most clearly how attitudes have changed. Employers should be aware of these important changes to the direction of travel and ready to comply with and implement them.